Wailin’ at The Whitney

(a feature story from 1995 on the historic Whitney Museum show)

Communities of creative minds exchanging ideas has been a dream of artists from the moment they first walked away from the other apes and got back to the land to set their soul free. The Lost Generation café klatch in Paris was cool, and San Francisco’s garden of flower pot parties in the ‘60s sounded like a hoot — but the most influential confluence since the Danube met the waltz took place in New York City in the late ‘40s and early ‘50s.

“Beat Culture,” the current show at the Whitney Museum of Art in New York City, is currently celebrating this zenith of fun through February 4th.

“Let me take you down, cuz I’m going too, through many fields, who knows what’s real, but I’ll try to point the highlights out.”

With Allen Ginsberg’s audio tour in your ear, the museum’s giant freight elevator doors open, and right in front of you is Jack Kerouac’s original scroll of On The Road, the Declaration of Independence of post-war America that Kerouac wrote in one 20-day chi-channeling frenzy in April 1951.

Kerouac wrote to Neal Cassady, his best buddy and the book’s main character, when he finished it: “I’ve telled all the road now. Went fast because road is fast — wrote whole thing on strip of 120 foot long tracing paper — just rolled it through typewriter and in fact no paragraphs — rolled it out on the floor and it looks like a road.”

This mythical dead sea scroll of rock ‘n’ roll has never been seen in public before, having been locked in Kerouac’s agent’s safe since it was first published. No one ever knew for sure if it really existed, but now we can see that not only does it, but Kerouac’s claim of spontaneous prose is upheld, as this opening of the crumbling unfurled scroll matches virtually word-for-word the final published text.

One endless roll allowed Kerouac to go on one — entering a subconscious trance where the artist was creating so quickly there was no time for regimented thought to alter pure expression. This notion of losing one’s self in the creative act, of flowing in a “stream of consciousness,” was the distinguishing difference between these artists and their contemporaries. While iambic pentameter, photo-realism, and Broadway musicals were lulling Beaver Cleaver’s parents into a saccharin stupor, the Beats were taking a chance on the inside without a script, and it turned out to be the cymbal crash of liberty in the jam of the century.

There on the wall is On The Road, and there on the road is a million new bands jamming their way into the future. Beyond the novel’s influence on writers, Ray Manzarek of The Doors put it bluntly: “If Jack Kerouac had never written On The Road, The Doors would never have existed.” After years of being Jim Morrison’s bandleader, Manzarek is now accompanying Morrison’s progenitor, Beat naturalist poet Michael McClure, in one of the most exciting live readings on the current poetry circuit. Besides them performing together as part of the exhibit, many paintings by McClure, Kerouac (his Buddha below), Corso, Ferlinghetti and others show how these writers worked in many media to express the exuberance they felt for life that just wasn’t coming through the Norman Rockwell covers on every newsstand of the decade.

Neal Cassady rapping with the Grateful Dead at the acid tests is also part of the exhibit as a video installation that’s continuously playing in the center of the show, loudly proclaiming the continuum of the Beats into The Beatles into all of rock ‘n’ roll. As Jerry Garcia put it, “It wasn’t a club — it was a way of seeing. It became so much a part of me that it’s hard to measure; I can’t separate who I am now from what I got from Kerouac. I don’t know if I would ever have had the courage or the vision to do something outside with my life ─ or even suspected the possibilities existed ─ if it weren’t for Kerouac opening those doors.”

Although Kerouac was the one who coined the term “Beat Generation,” wrote its Bible and defined its ethos, he secretly wanted “to be considered a jazz poet blowing a long blues in an afternoon jam session on Sunday.” His soaring sentences were taken directly from the Bird songs he was listening to on a nightly basis in Manhattan.

Playing throughout the multiple floors of the exhibit is the music created in the small clubs on 52nd Street or Minton’s Playhouse in Harlem, a nickel subway ride from the Beats’ Greenwich Village and Morningside Heights haunts. Charlie Parker, Dizzy Gillespie, Thelonious Monk and later a young Miles Davis and John Coltrane were blowing apart traditional jazz and improvising solos at double the tempo of the rhythm section. It demanded the perfectly pure channeling of a disciplined voice combined with the courage to throw everything you knew out the window for that one shot at sunburst glory where the golden soul breaks through the clouds and the god-like voice inside all of us comes flowing out in clear honest truth.

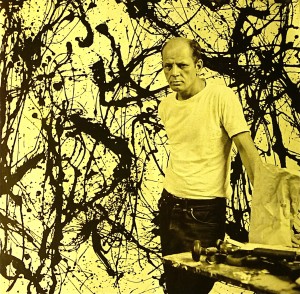

Back down on 8th Street, and then later at his retreat on Long Island, Jackson Pollock was busy inventing nonobjective abstract expressionism by going “into” his paintings ─ dancing hypnotically, weaving chaotically, creating quixotically harmonious flows on his giant canvases in a spontaneous trance of focused freedom.

“It was great drama,” a friend of his said of watching him work. “The flame of explosion when the paint hit the canvas; the dancelike movement; the eyes tormented before knowing where to strike next; the tension; then the explosion again.” As Kurt Vonnegut saw it, the reason Pollock’s work lasted was because “it celebrates what a part of the brain can do rather than what pictures should look like.” Or is that Kerouac or Bird he’s talking about? As Pollock himself put it, “When I’m in my painting, I’m not aware of what I’m doing.”

Also on the walls are several photomontages by the godfather of punk, William Burroughs, as well as his paper cut-ups, and Naked Lunch manuscript. And there’s the great New York poet, prankster and artist Gregory Corso, who contributed a hypnotic 3-D collage of every major city in Europe, as well as his notebooks and portraits of people he knew. “Hey!” he yells out at the opening night party. “That’s one of mine,” he says, squinting closer at his Portrait of Robert LaVigne. “Aaaa, doesn’t even look like the guy,” he said, waving his hand. “Come on girls,” as he walks away with his harem.

Over at a loft on 14th Street, Julian Beck and Judith Malina formed The Living Theater, whose photos, paintings, script outlines and filmed performances are part of the show, as they invited artists to mingle in performance and life, encouraging actors to improvise the essence of their characters instead of performing the same lines every night. And speaking of parties, theirs were legendary — there’s photos of Mailer and Ginsberg going at it again; there’s O’Hara, Kline, and Kerouac all drunk again; there’s Mingus jamming with Patchen, and Ferlinghetti reading Coney Island of The Mind; there’s Beck’s collages now hanging on the wall at the Whitney Museum; there’s hope.

And this new style of improv acting starting in New York soon took over Hollywood as Marlon Brando, James Dean & others began improvising many of the best scenes of the decade. Dozens of these gems are playing all exhibit long in the museum’s theater, including Rebel Without A Cause (1955). Dean’s co-star in that, Dennis Hopper, whose private art collection contributed greatly to the show, told the story of how Dean improvised that whole opening scene of Rebel — picking the wind-up monkey off the set and playing with it as a baby might, then wrapping it in a paper blanket. That single bit of subconscious, spontaneous acting has been studied by film students the world over for everything from its personification of the boy/man/baby torn-between-worlds dilemma, to its children-as-wind-up-toys-of-their-parents theory which set the stage for the film’s drama, as well as the generational conflict that followed.

The single coolest document of the Beats is also on view — the 28 min. independent film Pull My Daisy. Shot in 1959 by Robert Frank at painter Alfred Leslie’s loft starring Allen Ginsberg, Gregory Corso, and the painter/musician Larry Rivers. The film was shot without sound then narrated by Kerouac who improvised all the dialogue and storyline in a beautiful poetic funny vocal solo like Robin Williams on a double-shot of Walt Whitman.

It’s hard to fully appreciate what these artists were doing back then because it’s so much a part of our life now. Like soloing. But this was the transition point where Bob Hope, Louie Armstrong and Robert Frost morphed into Marlon Brando, Charlie Parker and Allen Ginsberg. What changed was their perception of the limitations of art. Each of the pioneers in this exhibition took the framework of the novel, play, canvas, or song, and said, “No rules ─ just purely transmit the songbird voice within without restriction but flow forever clear, Sweet Chariot.”

By ignoring the limitations of the canvas’s frame, the paint and painter were free to fly all around it. So too a song in Charlie Parker’s horn, an actor on The Living Theater’s stage, or a page in Kerouac’s typewriter. Not only did Jack eliminate paragraphs and page endings, but traditional narrative as well by telling one elaborate legend that ultimately ran through all of his books, a single story weaving like a double helix through all of life, illuminating truths that were beyond contrived literary pretension. It was joy in art. It was jamming. It was jewel mining in the fifth dimension.

There are historical precedents for each piece of this story — but they never came together in one place. The Italian Renaissance is the obvious comparison for multi-disciplinary revolution, but there’s not many of those cats around anymore. Van Gogh and the Impressionists were onto it, as were William Blake and Walt Whitman in their singing the songs of themselves. Yeats’ trance writing opened the door, and Joyce’s wordplay made it worth walking through. Emerson’s Self Reliance was the hard surface of the road, and Huck Finn walked along it whistling its tune. But that’s jumping continents and centuries. This renaissance took place on the same New York island over the same five years.

And as this historic Whitney show makes joyously clear, these guys were articulating in the late 40’s and early 50’s what we’re still experiencing today. This is the risk-taking avant-garde community’s direct cultural lineage. And this interconnecting story of writers, painters, musicians and actors will go on endlessly like an ever-expanding web site.

Gathered for the first time are the words, paintings, photographs, music and movies from one of art’s golden eras, when Pollock danced, Jack flew, Allen howled, and Bird blew. Some mop-tops copped the name, and the rest of the revolution was televised. But if you want to see how we got here from Ozzie and Eisenhower’s Conformity Generation, the cats are wailin’ at the Whitney through February 4th.

==========================================

For an excerpt from my book about the ’82 Kerouac Conference in Boulder — check out Meeting Your Heroes.

For more from the Boulder Beat Book — check out Who All Was There.

For more connections between The Beatles and the Beats — check out the time George Harrison saw Michael McClure’s The Beard and was raving about it to McCartney.

For a vivid account of being at the historic “On The Road” scroll auction — check out The Scroll Auction.

For a story about the London “On The Road” premiere at Somerset House — check out this sex & drugs & jazz.

For a great story of the world premiere of the new shorter final version of “On The Road” — check out this Meeting Walter Salles Adventure!

For a complete overview of all the Kerouac / Beat film dramatizations including clips and reviews — check out the Beat Movie Guide.

For a story about Henri Cru’s birthday — check out The Legend Turns 70.

For a beautiful poem to Carolyn Cassady on her birthday — check out the Carolyn Cassady Birthday Poem.

For an inspiring description of being at a Beat jazz-&-poetry reading in Greenwich Village — check out Be The Invincible Spirit You Are.

==============================================

by Brian Hassett

karmacoupon@gmail.com BrianHassett.com

12 responses so far ↓

1 Hugh Reilly // Jan 27, 2013 at 11:04 AM

Awesome Brian….great to see this again after all these years!

2 john j dorfner // Jan 27, 2013 at 3:03 PM

great article… went to Rocky Mount a few days ago. they have a new plaque right off main st for Monk…and a piano…an actually real piano setting there under the sign. i set down and played some Monk Chops on it. it was cold and windy but i had too many goose bumps from ‘thrills’ to even real the cold. i’ll send you some photographs. cheers…Road coming to the Raleigh movies soon. wow!

3 George Summers // Jan 28, 2013 at 2:19 PM

Write more! That’s all I can say!

4 Brian Humniski // Jan 28, 2013 at 7:48 PM

Wow! What a great account! Thanks for taking me there!

5 Holly McAlister // Jan 28, 2013 at 9:04 PM

Sorry I missed this show. One of my biggest regrets.

6 Roy Moore Jr. // Jan 29, 2013 at 2:52 PM

Me and the Mrs. caught this is San Francisco at the DeYoung. What a treat it was to see the scroll at long last. The exhibition book they made is a prized part of my collection. Thank you for reminding me of that magic time and place.

7 Larry Dublin // Jan 30, 2013 at 6:25 PM

This happened around the same time as one of those big NYU conferences … back in the good old days when everyone (almost) was still alive and kicking. It’s so good at least one museum did a major show on these guys. Thanks for taking me back to it. 😉

8 David Moran // Jan 31, 2013 at 3:35 PM

You can write your ass off! Wish I had seen it. But this is the next best thing!

9 Laura Lansing // Feb 2, 2013 at 10:46 AM

“The mythical dead sea scroll of rock ‘n’ roll” — you got That right! We just saw it a couple months ago in London. It made you want to dance just being in the same room with it, but it was also sacred like a church. Weird. Anyway, thanks for reminding me and bringing all this Beat stuff to life for us!

10 Damian D'Aguila // Feb 3, 2013 at 8:58 PM

Wow! This sounded crazygood! I can’t believe this even happened. What a trip it must have been to walk around so much space surrounded everywhere by Jack & Friends.

11 Robert Morican // Feb 7, 2013 at 12:45 PM

Love all the Pollock and painting stuff! As an artist, it’s great to be reminded of these guys who saw no edge to the canvas. They were the ultimate freedom of expression. Look out canvas, here I come …

12 Dan Neil // Feb 16, 2013 at 7:54 PM

This is why I keep coming back to your site. 🙂

Leave a Comment